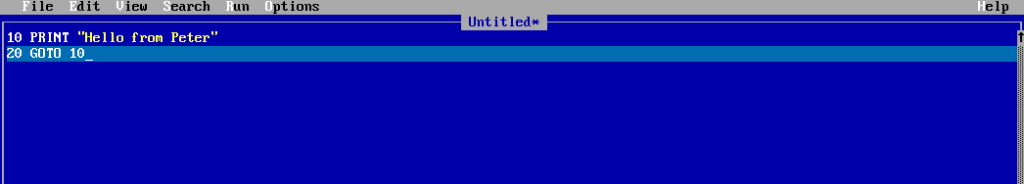

[Note: This started as a Bluesky post from someone regretting that we’d never get a Discworld novel that dealt with generative AI. They proposed the wizards creating Large Language Monsters, which ate everyone’s stuff and then regurgitated it, until Vimes arrests them all for being stupid… which is an absolutely terrible idea for a Discworld book.

Still, I did like the idea of a Discworld version of AI, and I do like writing as other people, so I wrote a couple of scenes.

I’ve been reading Discworld for most of the time there has been a Discworld (I bought The Colour of Magic after reading a pre-publication review of Equal Rites in White Dwarf magazine) and I am painfully aware that I am not the writer TP was, but it was fun and oddly comforting to try writing using his voice, so I kept on going a bit. This is the stuff I put on B’Sky, plus some of the additional stuff I wrote. If people like it I may write a little more, if they don’t like it then I’ll probably write more anyway… because I’d be lying if I said pleasing you was high up my priority list.

The problem with this story (other than the low-quality writing) is that Hex, the Unseen University’s thinking-engine, seems like a natural component of any story about AI, but Hex has already been shown using natural language on numerous occasions, even if you don’t count the various Science of Discworld books as canonical. My solution to this is not to care about it. Bugger it, if TP can get away with saying that the Patrician from The Colour of Magic is the same bloke who appears in later books then you can shut up and swallow this.

Finally, I met somebody on a bus who said he was a lawyer, and he said this was all legally OK. If it’s not then you have to take it up with him.]

Scene 1

It was a bad winter. Even in the Ramtops, where winters were often lethal but otherwise lives were long, people were saying it was the worst in living memory. At night wolves were coming into the tiny villages nestled into the mountains, which was unheard of, Ramtops’ wolves, their intelligence heightened by the strong magical field in the area, having long since learned to avoid humans, unless they had them heavily out-numbered, because wolves that didn’t learn this lesson tended up end up as a matching hat, slippers and gloves set. On the plains below the mountains the winter froze the fertile soil and when it reached Ankh-Morpork, the greatest, or at least most noticeable, city of Discworld it hurled tiny icy daggers down the thoroughfares, turned every street into a patchwork of tiny skating rinks, and on the coldest nights got within 20-degrees of the city’s many street vendors deciding not to get out there and sell.

On such a night, Lance-constable Tom Puntpole of the Ankh-Morpork City Watch was walking his first beat but had the good fortune to have Sergeant Detritus accompanying him. There wasn’t a man, dwarf, or none of the above in the watch who didn’t appreciate having Detritus on patrol with them. Even amongst other trolls he was known as someone not to mess with, which meant that situations which might, in smaller hands, have become violent, tended to remain very polite and to get resolved with no sudden movements. Additionally, Detritus’s immense bulk also made him a very convenient weather-break, and any watchman smart enough to know which way the wind was blowing could use him to avoid the worst effects of gales, rain, snow, and quite possibly meteorite strikes.

Now, with winter reducing the city’s temperatures to those more normal for the high ice-fields, where trolls had evolved, it also meant Detritus was smart[1], and as such he’d requested[2] that his young charge be given the beat that took in the Unseen University.

Throughout the year the area immediately around the university was low in crime, because those taken as easy marks by pickpockets, muggers, and assorted members of the street-crime fraternity might also turn out to be a dab hand with fireballs. The lack of crime meant the area was deemed by the watch to be an ultra-low commission zone and the Thieves Guild avoided it altogether, because of the combustion charge. On cold nights, however, the beat past it was the most sought after, as it ran alongside the university’s ever-expanding High-Energy Magic building, which now formed part of the boundary wall. Whatever went on in the building, which was firmly beyond the watch’s jurisdiction, the wall radiated a wonderful warmth which provided comfort for any watchman too cold to care that the wall also vibrated, changed colour, and occasionally spoke to you.

‘How long have you been a copper, sarge?’ asked Puntpole as the pair proceeded by the wall.

‘Two thousand, six hundred and fourteen nights[3],’ replied Detritus, without hesitation

‘Do you think I could make sergeant?’

‘A smart human like you? Sure. Two years, maybe less if you get an offer from one of the other plains cities. Or further afield, even. I heard they’re looking for sammies as far as Uberwald these days. Is being a sergeant what you want?’

Puntpole sighed. He just wanted to feel that there was a future,e but he’d always struggled to imagine a world past the present with a him-shaped space in it. During his childhood he’d met many adults who seemed to regard asking him what he wanted to be when he grew up as polite conversation, but the question had always filled him with dread. Nothing he’d ever tried, irrespective of his talent at it, had struck him as the thing he was meant to do with his life. He’d joined the city watch because it had a generous fund for widows and offered decent pay, a smart uniform, a time off to help him find the lucky lady who could one day be his widow, but even now, on his first beat, he couldn’t form a mental image of himself doing it in two years’ time, or in a year, or even tomorrow. He felt like a jigsaw piece that hasn’t quite fitted into every spot it’s been tried and is uncertain whether more sky needs to be filled in to find their spot or if they’re actually from a completely different jigsaw altogether.

‘What’s is occurring here, then,’ asked Detritus, interrupting his musings. Their proceeding had brought them to a group of three young men lounging against the wall. Basic training had taught Puntpole that this was contrary to the Public Loitering Act and as the three were clearly students it was likely they were also in possession of facial hair likely to cause a breach of the peace, carrying concealed offensive clothing, and probably underage thinking.

The three of them were gathered by the fire-door[4] of the HEM, which was propped open with a thick wad of paper.

‘Good evening, officers,’ said the oldest of the students, causing a large cloud of smoke to escape into the night air. He brought a device, about the size and shape of a hip flask to his lips, tipped his head forward onto its mouthpiece and inhaled deeply.

‘What’s that,’ asked Puntpole.

‘A new invention,’ replied the student proudly, producing another cloud, ‘Smoking without fire.’ He held the device up for inspection. ‘This chamber contains the essence of smoking, trapped in liquid form, and when I press this button here,’ he indicated, ‘A very small spell heats a tiny bit of the liquid, and I breathe in the vapour. Very tricky to get the spell size right,’ he concluded. Puntpole noticed that one of his eyebrows and a portion of his fringe were missing.

‘And it’s the same as smoking is it,’ asked Detritus.

‘Oh yes, all the benefits, without any of the problems. No looking for a light, not having to worry about your ‘baccy or papers getting wet in this weather, no having to roll up.’

‘What benefits,’ asked Puntpole, quietly.

‘We’re thinking of selling them outside the university. They’ve been very popular with the students,’ His two companions held up their own devices, which looked to have been hand-painted. ‘We’ve been trying to think of a name for them. Something that says it’s a quick and easy alternative to smoking. Something like… Smokeless Easy.’

‘Fast sucking,’ suggested one of the other students.

‘Vapour rapid,’ added the final member of the trio.

‘You think this is going to be a thing,’ whisper Puntpole to Detrius.

‘Dunno. Can you smell frying onions?’

Puntpole sniffed the air. ‘No.’

‘Then Dibbler’s not within half a mile. If there was a dollar to be made in this then he’d be here.’

The fire door opened, and a new wizard appeared, slightly older than the other three.

‘Come on, lads, smoke break’s over. We need you back inside. What are you doing here,’ he asked the two watchmen.

‘Just walking our beat, sir,’ replied Detritus, respectfully.

‘Great! We can use you for testing. Give me a question,’

‘Why,’ asked Puntpole.

‘No, we’ve tried that one. It doesn’t work well. Something a bit more direct.’

‘Who was it who held up the Royal Bank of Ankh-Morpork last Wednesday,’ asked Detritus, with a copper’s instinct and, because some ideas were lodged so deep in his mind that not even his current genius-level intelligence could lever them out, added, ‘Was it you?’

The newcomer considered this for a second before announcing, ‘Yes, that could work. Wait here!” The other students were ushered back inside, pocketing their vapour rapids as they went, and the fire door slammed shut, leaving the two watchmen alone in the night.

‘What was that about,’ asked Puntpole.

‘Wizards,’ said Detritus, dismissively, ‘Always up to something. Still, if it gives us a lead then Captain Carrot will be pleased.’

‘I heard that Commander Vimes was dead against using magic to solve crimes.’

‘Who’s using magic? We’re just asking questions,’ stonewalled Detritus.

There was the sound of a bolt being drawn, and the fire door reopened and one of the students reappeared.

‘Here you go, ‘ he announced, proffering a couple of sheets of paper and, as an afterthought, taking a quick suck on his vapour rapid.

Puntpole took the papers. ‘This is all print, like in the newspaper,’ he observed, ‘You haven’t had time to set two pages of print.’

‘Thanks for your help,’ replied the student, gnomically, and ducked back inside, closing the door behind him.

‘What was that about,’ asked Puntpole.

‘Wizards,’ repeated Detritus, resuming their patrol. Puntpole shrugged, tucked the pages inside his armour, and hurried after him.

Scene 2

Ponder had tried to explain the problem to the Arch Chancellor, this created new problems. Ponder was an extremely bright young man, except in the vitally important field of explaining what he understood to other people. Ridcully, while also possessing a formidable intellect, was a straightforward man to whom metaphor and simile were not a closed book, an undiscovered country, or a riddle wrapped in an enigma, but rather something he failed to understand so completely that Ponder was convinced it must a long-running joke at his expense.

‘Take this book,’ said Ponder, determined to persevere, and picking a book from the top of the pile next to him, ‘You wrote this book.’

Ridcully peered at the cover. ‘Carnivorous Butterflies of Howondaland,’ he read, ‘No I didn’t. It was written by Leopold the Diarist. It says so, right there on the front.’

‘You didn’t in this reality, but L-Space contains every book ever written in every universe, so it contains the version of this book that you wrote.’

‘Is this a trousers of time thing?’ asked Ridcully, suspiciously. Every encounter he’d had with the trousers of time had left him with the distinct feeling that he’d got the gusset.

‘Yes,’ exclaimed Ponder, hopefully, ‘In some universes things happened that led to you writing this book.’

‘What? The same book?’

‘Yes.’

‘And then this Leopold fellow copied it off me, did he?’

‘Ye- No, no. He just wrote the same book.’

‘Doesn’t sound very likely to me. I’m going to talk to Mr Slant about this. Can’t have people copying books I wrote in other universes without paying me for it.’

‘That’s the problem,’ said Ponder, spotting an opportunity, ‘If we connect Hex to L-Space then it will read your book about butterflies and a million other books you wrote in other universes as well.’

‘Right, well, that should be good for my sales then.’

‘Ah,’ said Ponder, coyly, ‘That’s a different problem.’ He flicked to a random page in the book and showed it to Ridcully. ‘Here, this is the Swallowtall Butterfly which is black and yellow, right?’

‘Right,’ agreed Ridcully, ‘Did I do the drawings as well in this book of mine? I’m really rather pleased with that one.’

‘But if Hex learns from L-Space,’ Ponder pressed on, ‘And you ask it what colour the Swallowtall is then it might tell you it’s purple and red.’

‘Ah, it would be wrong, then?’

‘No, because in the other universe, where you wrote the book, the Swallowtall might be purple and red.’

‘But when I drew it I’d lost my purple pencil, so I did it yellow instead? That’s a shame, I was feeling proud of that drawing.’

‘No, in this universe it’s yellow and black, in other universes it might be purple and red, and Hex will pick whichever answer is most likely.’

‘Right. So it gives you the wrong answer?’

‘No, Arch Chancellor, it will give you a right answer, you might just be reading it in the wrong universe.’

‘It seems to me this Large Language-‘

‘Multiverse,’ prompted Ponder.

‘Multiverse, is going to a great deal of trouble and expense to generate wrong answers. We’re a university, Mr Stibbons, we’re already full of students who can be relied upon to give us a wrong answer, the difference being that they pay us to put up with it.’

Scene 3

The Patrician stared over his steepled fingers at Mr Slant, the city’s foremost lawyer.

‘Are you suggesting, Mr Slant, that this contraption of the wizards should be allowed to read the books for free?’

‘Not as such,’ replied Mr Slant, who was only comfortable with the word free when it pertained to removing one of his lucrative clients from legally mandated accommodation. ‘The payment would be in the form of the inestimable boon this new technology would provide to the city.’

‘The boon provided by,’ the Patrician paused to check his notes, ‘The machine that gives wrong answers?’

Mr Slant shifted uncomfortably. He did not like having the wizards as clients. Traditionally the wizards got around the law by ignoring it and directing any enquiries about its applicability to them into a discussion about how using magic to, say, turn someone into a toad was frightfully tricky, while turning them into something that wished it was a toad was child’s play.

He was also unconvinced by the merits of their case, which was a scruple which had never before bothered him in his long, undead, life. While a great many of his clients came from those who had been very quick to give wrong answers to questions such as, ‘Where were you when the murder happened,’ he didn’t see the purpose of a machine to do so. For a start it didn’t have any pockets.

‘Havelock[5],’ he shrugged, ‘You know how these things arise from time to time; the Golem liberation movement, the printing press, the clacks, and so on. It’s probably best to keep out of their way and let them run their course.’

‘As with the moving pictures fad,’ asked the Patrician, sweetly. ‘I understand you missed the affair at the time, but you probably heard about the city nearly being destroyed by a 50ft woman.’ Not a muscle moved on the lawyer’s face. There was no possible way for the Patrician to know about Slant’s private work to see if the lucrative legal side of the business could be somehow resurrected, but without all the dangerous and unnecessary messing around with actual moving pictures, actors, or anybody in any way creative. Still Slant swallowed unnecessarily.

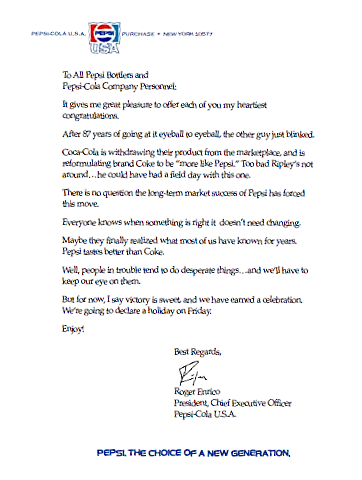

‘Anyway,’ continued the Patrician, after slightly too long, ‘The Guild of Authors[6] have written to me about this matter. A beautifully crafted note, with quite the twist at the end. They feel that what the university is proposing is no more than common theft. The Guild of Poets is completely averse to it. The Guild of Portraitists and Sculptors have also demonstrated to me that they look on it with anger, and perhaps touch of sadness.’

‘Have the Progressive Artists Guild performed a dance about the injustice,’ enquired Slant, with a dust-dry chuckle.

‘No,’ replied the Patrician, smoothly. ‘They have sent me a note reading, “Don’t let that bastard Slant do this.” I do so admire people who can separate their passion from their business interests.’

Scene 4

Puntpole had never been inside the Great Hall of the unseen university before. It seemed to be mainly a conveniently large space for wizards to argue in. The small team of wizards next to him had been charged with decorating the ceiling for the occasion. He’d listened in as, via each of them talking over all the others, they’d eventually agreed to use a spell called Patmoore’s Sky Alight, which he’d gathered was supposed to make a starry vista appear overhead, before they each in turn admitted they didn’t know that one. This had been followed by a lot of talk of indoor firework spells, which is also turned out none of them had to hand, and then a heated discussion about whether fireballs would work just as well and whether there’d be any collateral damage. They were now arguing over which of them should go and find some crepe paper and glue. A little further away the Arch-Chancellor, resplendent in his official robes, was having a conversation with a harried looking younger wizard, which Puntpole could only hear half of, thanks to the Arch-Chancellor’s lack of an indoor voice.

“I don’t like it Stibbons! Wands smack of conjuration. You start off thinking one is jolly useful and before you know it you’re pulling rabbits out of hats at children’s birthday parties.” There was a pause while the wizard called Stibbons replied, with something which evidently didn’t please Ridcully, “Point it at my throat? Are you mad? You won’t last long as a wizard if you go around pointing magic artefacts at your head[7]?” Stibbons replied, then took the wand, pointed it as his own throat, and spoke.

“Testing.” Stibbons’s voice sounded clearly throughout the hall, momentarily pausing dozens of wizardly arguments. The Arch-Chancellor grabbed the wand, studied it and then held it to his own throat.

A few minutes later, once the tables had been righted again, some students had cleaned up the broken glass, and the unfortunate wizard, who’d been hit by a chunk of stone when a decorative cherub exploded had been carted, off, Puntpole leaned back against a pillar, while he waited for the ringing in his ears to stop. The other members of the city watch were clustered in their friendship groups and, as usual, Puntpole felt there was no place for him. He’d rather have been walking a beat, but Captain Carrot had been very insistent that the watch’s newest recruit should be present for Command Vimes’s celebration dinner. It was at least a familiar feeling. In everything he’d tried, he’d always got the distinct impression that others knew he didn’t belong there.

“BELIEVE ME, I KNOW THE FEELING,” intoned the figure that he suddenly noticed was standing next to him. This wasn’t a watchman, as he was wearing a robe instead of armour, but also wasn’t a wizard. There was no way this figure had been eating hearty dinners for fifty years, or indeed ever. They also tended not to be seven feet tall, and carrying a sythe.

“Am I about to die,” he gulped.

“IT IS A POSSIBILITY,” agreed Death.

“How,” asked Puntpole. The guards were shuffling into their positions for the opening of the celebration, the wizards were finalising the décor and trying to stop the ceiling raining, and he doubted that anybody anywhere thought enough of him to be considerate enough to arrange for an assassin for him.

“YOU WILL FALL TO YOUR DEATH.”

“Here,” questioned Puntpole, giving the very solid flagstones a tap with his boot.

“IN TINLID ALLEY,” replied Death, a shade uncertainly.

“Tinlid Alley? That’s half a mile away. How can I be about to die there?”

“DO YOU KNOW WHAT A QUANTUM LEVEL EVENT IS?” An elderly man, sweeping up the last of the glass and cherub, passed through Death, apparently without noticing.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” boomed the voice of the Arch-Chancellor, as he rose to his feet. The rest of the hall fell into silence. He picked up a few sheets of paper, which bore a striking resemblance to those that had been thrust into his hands behind the High-Energy Magic building. “We are gathered here tonight to commemorate Samuel Vimes,” read the Arch-Chancellor. Vimes, sitting next to him, tried to grimace as slightly as possible.

“We commemorate Sir Samuel,” Ridcully’s brow furrowed slightly, “On this, the tenth anniversary of his death.”

The room waivered a bit, as if in a heat haze. Puntpole felt like he was staring at an optical illusion, he could clearly see the hall decked out in celebratory colours and Vimes giving Ridcully a puzzled look, but he could also see the sombre colours everywhere, and Vimes’s spot taken by a large wreath.

“THIS IS A QUANTUM LEVEL EVENT,” intoned Death, “A GREAT MANY THINGS ARE UNCERTAIN RIGHT NOW.”

“What should I do,” yelled Puntpole.

“TRY TO STICK TO WHAT YOU ARE CERTAIN OF IS MY ADVICE.”

What Puntpole was certain of that moment was that something was poking into his back and a voice right behind him had just said, “This is a pistol crossbow, mister. Put your hands up,” and then the hall was gone and he was falling towards what he assumed were the cobbles of Tinlid Alley.

After a lifetime of crime fighting, it was Commander Vimes’s opinion that there wasn’t a single tool in the police officer’s arsenal more powerful than a criminal’s over-confidence. Anybody planning to crime who truly, deep in their heart, believed that the stupid coppers would never catch them already had one foot in a cell. It irked Vimes that efficient coppering kept leading to an under-supply of over-confidence. When rumours got out that the watch had a werewolf, who could track the smell of guilt, or gargoyles who could watch a given location for days, or a gnome who could ride a hawk and see the city from half a mile up, those of a criminal bent didn’t decide to give honest living a try. No, the bastards started being clever.

One of the weapons the watch had honed to counter this was Sergeant Fred Colon, a one man campaign to prove that the watch could still be lazy, stupid, keen to suspect the first ethnic minority that came to mind, and open to the micro-bribes of free beer, tobacco, and baked goods. Every time that Vimes sensed that the criminal minds of the city were getting under-confident he sent Colon out on a few extra patrols, to build distrust in the police within the community.

Amongst the rank and file of the watch what Colon delivered was rather more more earthly. None of the watch, up to Old Stoneface himself, could remember a time when it hadn’t included Sergeant Colon, and over the course of his long career he’d learned what watchmen liked. Those arriving back at a station he was running, as Sergeant Detritus and Lance-Constable Puntpole now did, could be sure of a roaring fire, a strong mug of tea, and no difficult questions viz-a-vis a slight odour of ale, a pocketful of baccy, or a few pastry crumbs on your collar.

The wave of heat hit Puntpole as soon as opened the door. After a long patrol in the freezing weather it was like stepping into a furnace. The air in the doorway, where the cold front met the Colon-heated blast, shimmer like a desert mirage, and hung with the scent of tannins and biscuits. Detritus, who had spent the last mile of the patrol constructing an elegant and simple proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem with every rhythmic step, felt his intelligence being stripped away now that there was no more room to march on.

In long-standing watch tradition, the pair of them grabbed a mug of something hot and didn’t speak until it was drained.

‘What’s on dem papers the young wizards gave you,’ asked Detritus, once this ritual had been completed.

Puntpole retrieved the folded papers, now slightly dampened at the edges by inquisitive snowflakes and unfolded them.

‘Your many years people have created theories about who robbed the Royal Bank of Ankh-Morpork,’ read Puntpole.

‘It can’t have been that many years,’ said Detritus, ‘It only happened last Wednesday afternoon.’

Puntpole shrugged and continue reading. ‘Evidence now suggests that the crime itself was committed by Havenot Bugler, Karl Smiterson (commonly known as ‘Shins’), and Robert Levees, all residents of the Shades district of Ankh-Morpork.’

‘I don’t reckon it was Bugler,’ chimed in Colon, who’d been listening with interest, ‘He doesn’t do bank jobs these day, what with him having been buried up at Small Gods for the past three years.’

‘O, dat’s a good alibi,’ offered Detritus.

‘There’s more,’ said Puntpole, ‘Although these men were the ones who carried out the robbery itself, the complex nature of the crime and the choice of target suggest that it was masterminded by criminal genius Professor Moriarty.’

‘Who’s Morry Arty,’ asked Detritus.

‘Probably short for Maurice,’ suggested Colon, ‘Maurice Arty. Doesn’t ring a bell.’

‘I don’t think it’s Maurice,’ said Puntpole, ‘It’s all one word, Moriarty, look.’

‘I knew a Quarry once,’ mused Detritus, as Sergeant Colon walked round to look at the paper Puntpole was holding.

‘Ah,’ exclaimed Colon, triumphantly, ‘This is print, like the newspapers use. They make mistakes all the time. Remember last week, when that hublands king visited the city, the one who commanded the tide not to come in? Well, The Times spelled his name wrong. I nearly widdled meself when I saw it. They had to print an apology the next day. Apparently, the Patrician was furious, what with the king being here on a goodwill visit[1]. I heard he had the palace guards arrest the editor and…’ Here Colon paused and looked around to see who was listening with such an exaggerated conspiratorial air that half a dozen watchmen on shift-change, who had been paying no attention to the conversation, leant in to hear the whispered details of what the Patrician did.

‘That can’t be right,’ countered one of their number, once Colon had finished his lengthy description. ‘I saw Mr de Worde this morning and he was fine. Wasn’t even walking funny or nothing.’

‘Well, I expect he’s been told to hush it up,’ countered Colon, ‘When the Patrician makes an example of someone he doesn’t want everyone knowing about it, does he?’

There was a moment of silence, while the assembled guards considered this wisdom.

‘So,’ continued Colon, cheerfully, ‘Professor, eh? Now, that could be the university, or the Teacher’s Guild[2], or… ‘ He paused and a worried look crossed his face. ‘Oh no! Not them bastards.’

‘You alright, sarge?’

‘It’s a misprint, isn’t it,’ stammered Colon. ‘It’s no Morry Arty. It’s Professor Merry Arty, and that’s a clown name if ever I heard one.’

‘Are you sure, sarge,’ asked one of the watchmen, nervously. No-one who’d ever set foot inside the Fools’ Guild ever wanted to do so again.

‘You mark my words,’ replied Colon, ‘This one is going to turn out to be a real three pie problem.’

[1] So much goodwill was exchanged that the king needed 3 carts to carry his new stash of weapons. He left Ankh-Morpork with an agreement of favourable terms on future weapons purchase, if he protected clacks towers in his territory, and also with, like most visitors to the city, the lingering taste of sausage in a bun in his mouth, an embarrassing rash, and considerably less gold than he arrived with. However, not being a Morporkian-speaker, the question of why the misprint of his name had caused such hilarity would remain forever a mystery to King B’totom.

[2] The sign outside the Teachers’ Guild, reading Teacher’s Guild, was their principle recruiting tool. Many a pedant had rung their bell to correct the error, received a sharp tap to the back of the head, and awoken chained to a year three geography classroom.

[1] The silicon-based troll brain is optimised to run at very low temperatures, and in such conditions they can achieve intelligence surpassing that of humans. This was why Commander Vimes had recently recruited three trolls with particularly sharp sub-zero minds to form a small unit who worked from an office in the city’s freezing pork futures warehouse, re-examining reports on old crimes that had baffled the watch. Technically they were the cold cases team, but to the rest of the force they were simply known as the new bricks.

[2] People tended to grant Detritus’s requests, as it might be hurtful to make him insist.

[3] Trolls, as a naturally nocturnal species, did not count in days

[4] As the HEM housed a great deal that was secret, dangerous, or at least unwise, Ponder Stibbons, the member of the university facility who oversaw it, had gone to great trouble with its security. The main door lock was a sturdy metal box, into which the aspiring entrant had to insert a punch-card. This turned on a light, which shone through the holes in the card and awoke the team of imps who lived in the box. They compared the pattern of lights to the diagrams they’d been given for valid users and, if there was a match, noted which one it was in a tiny log and then unlocked the door. A final imp was used to deliver a buzz or a beep sound effect, to indicate success or failure. This led those seeking ingress into a small room, with a door ahead of them that sported an eye, crafted of quart and ruby, which scanned their thaumatic signature, unique to each wizard, before dropping a counterweight that lifted the heavy steel bar behind the door. Passing the magelock led into a larger room, containing Pascoit the troll, who struggled to tell one human from another, but who could be relied upon to remember a new secret word every month and trusted to deal harshly with anyone who couldn’t do likewise.

In his design of this security system, Ponder had failed to take into account how much trouble all this would present to someone who just wished to pop outside for 5 minutes, so within a week of its installation a fire door had appeared in the rear wall of the building, to let the smokers out. It was secured by a 30 pence bolt from the Street of Cunning Artificers.

[5] Mr Slant was one of the few people to address the Patrician by his first name. This may be because, as a zombie, he had less to fear than most from a ruler with the absolute right to have anybody he wished put to death, or it may be that his sharp legal mind had reasoned that a man who allegedly read secret reports on everything that happened anywhere within the city couldn’t possibly find his given name to be in top one million most objectionable things he’d been called.

[6] Fiction writing on Discworld, which walks the tightrope between the real and unreal, is a dangerous occupation. A skilled writer may find that he has literally brought his creation to life. The Discworld’s writers tend, therefore, not to go out of doors more than they need to, especially if they have created cunning and dangerous antagonists, lest they become a victim of their own success.

[7] Until relatively recently, advancement through the ranks of wizardom was achieved by ensuring one’s immediate superior was not so much impressed as interred. There were times in the university’s past when senior wizards had a body-count exceeding that of their counterparts in the Assassins Guild. Ridcully’s tenure had ended this practice, as he seemed unkillable, always carried a loaded crossbow on his person, and nobody who knew him wanted to risk being haunted by his ghost. Even so, a wizard who accepted a magic item from a subordinate and was willing to follow instructions to point it at their head and then say the magic world was a wizard who was not going to go very far, except maybe in pieces.