If, like me, you’re British then your knowledge of New Coke is likely to be (a) it was a massive failure, (b) everyone hated it, (c) it was a terrible business decision, and, if your go-to reference for it is The Simpsons then probably (d) the person responsible for it ended up down-and-out, living in a railroad yard with Homer’s half-brother, Herb.

Of course, unless you’re new to the Internet, my very listing of those facts should tip you off that I’m about to debunk them.

Let’s start at the end of the list. The person most responsible for New Coke was Coca-Cola’s chairman and CEO, Roberto Goizueta, who’d worked his way up from, aged 22, responding to a “Help wanted” ad, placed by a Coke bottling factory in his native Cuba, to running the company before he was fifty. He was not fired for the New Coke fiasco. Nobody was, but especially not Roberto, who continued to run the company until his lifelong smoking habit caught up with him and he died of lung cancer, exactly one month before his 66th birthday, in 1997.

As you might expect, such a high-flier wasn’t given to terrible business decisions. His previous one, Project Triangle, which gave the world Diet Coke, hadn’t done so badly. The truth is that Coca-Cola had their backs against the wall. At the end of the second world war, for every 5 soft drinks sold in America, 3 of them were Coke. By the start of the 80s it wasn’t even 1 in 4, and Pepsi were gaining ground quickly. Pepsi was far more popular with Generation-X, while Coke’s customers were boomers (literally, people born in the baby-boom, not just old people generally) and the oldest of that generation were about to hit 40, which Coca-Cola feared would mean them abandoning high-sugar drinks and looking for healthier alternatives.

Coke still marketed itself as “America’s favourite cola”, which, as the best-selling cola in the country, it was. However, it had twice as many vending machines as Pepsi and a strangle-hold on fast-food outlets, particularly McDonald’s. In grocery stores, where buyers had a choice, Pepsi was beating them. Coca-Cola spent more on shelf-space, more on advertising, and still Pepsi was creeping up on them.

Pepsi advertising was showing people taste-testing colas, and then being amazed when they picked Pepsi as their favourite. “Will you take the Pepsi challenge,” asked the commercials. Coca-Cola’s own market research told them the same thing; in blind taste-tests, Pepsi out-performed Coke by 10-15 points. It wasn’t even a close battle. Coca-Cola, not unreasonably, concluded that as they were losing a war of taste, they had to change Coke’s taste to win, and that is made sense to tell people they were changing. After all, the goal was to get more people drinking the stuff.

Why, then, did they introduce a product that people hated? This question really played on my mind when I started working in market research, 15 years ago. Had New Coke been market research’s greatest failure?

First off, it’s hard to overstate how seriously Coca-Cola were taking the challenge of finding a new flavour for Coke, named Project Kansas, as contemporaneous documents show.

In its size, scope and boldness, it is not unlike the Allied invasion of Europe in 1944. This is not just another product improvement, not just a repositioning or new product introduction. Kansas, quite simply, can not, must not fail.

Coca-Cola wanted their new taste to be tested on every demographic from every part of America. If you don’t work in market research then, let me tell you, taste testing is a pain in the arse. You can’t just line people up, give them two sippy cups, and keep a tally of which one they prefer. You need to ask them a whole load of demographic questions; how old are they, where are they from, are they a Coke drinker, a cola drinker, are they the main shopper, etc. Then you have to ship supplies of your product and your competitor’s brand all over the country, it has to be stored correctly and served correctly. Then you have to keep a daily eye on the results, if you have one location or even one interviewer who is getting anomalous results then you have to find out what’s wrong. And, remember, this is all happening in the mid-80s. Sure, you can use a computer to compile and tabulate the results, but your information distribution process relies on both manual data entry and fax machines.

If you’re talking about a market the size of America, and you want decent sized demographic sub-sets, then you’re talking about a minimum of, say, 5,000 tests. That is a huge logistical exercise, and a huge expense.

But this was Coca-Cola’s version of winning WWII, so they didn’t do 5,000 taste tests.

No, they did 190,000 taste tests.

And people loved New Coke.

Coke was losing to Pepsi by up to 15-points, New Coke beat it by 8 points. Even established Coke drinkers preferred the new version to the old, more so in non-blind tests, where they were reassured that it was still Coke they were drinking.

Multiple books have been written about New Coke’s failure, and many of them at this point talk about the methodological flaws of taste-testing. What tastes good as a 25ml sample doesn’t necessarily translate into what you want to drink a ½ pint of with a meal, with such an established product it’s hard to separate the branding from the taste, even the colour of the packaging has an effect on how consumers perceive the flavour, etc. The truth, however, is that when New Coke launched the public reception of it was exactly in line with the market research. People liked the product, most Coke drinkers said they’d continue to buy it, sales of Coke went up about 8%. New Coke was a really successful failure.

To find out what really went wrong, let’s wind back to a bit before the product launch. In a gift to all future chroniclers of this topic, Coca-Cola held their final launch/don’t launch meeting on April Fool’s Day 1985. In this meeting at least two serious mistakes were made. The first, and the only part of the New Coke story that Roberto Goizueta ever admitted was a mistake, was that the press launch would make no mention of Pepsi or the Pepsi Challenge. Coca-Cola would not admit they were changing their taste because Pepsi tasted better. The second was to have the press launch in Pepsi’s home, New York, rather than Coca-Cola’s in Atlanta. Both of these decisions would contribute, in part, to New Coke’s failure.

It was also decided in the meeting that the press launch would be on Tuesday 23rd April, 1985, with the invitations to the press going out the preceding Friday. This gave Pepsi as little time as possible to prepare their response.

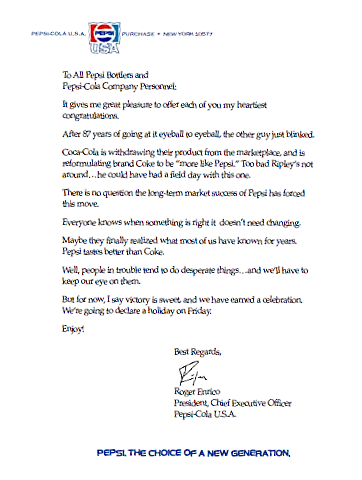

Pepsi, it turned out, didn’t need much time, because on the day the invites went out their Director of Corporate PR, Joe McCann, had an idea so good that he nearly crashed his car. Pepsi were genuinely worried that an improved Coke could derail their taste-test advertising. After all, the Pepsi Challenge didn’t really work if Pepsi didn’t win it. McCann spotted a way to turn the situation to their advantage. He pitched his idea to Pepsi’s CEO, Roger Enrico, and Enrico sent a letter to every Pepsi employee, which was then taken out as an advert in newspapers across America on the morning of New Coke’s launch. Pepsi unilaterally declared that they had won the cola wars.

“The other guy just blinked,” went on to become the title of Enrico’s autobiography, and that letter changed the narrative completely. When Goizeueta opened Coca-Cola’s press conference with the line, “The best has been made even better,” the very first question from the floor was, “Are you 100% sure that this won’t bomb?” Goizeuta, who wasn’t a naturally gifted public speaker to begin with, found himself under fire and, in trying to stick to the decision from the April 1st meeting, allowed himself to be backed into the ridiculous position of claiming that he’d never heard of the Pepsi Challenge.

The press saw the opportunity for a story, and they had some help. A few paragraphs ago I said that the public reaction was exactly in line with market research… well, it was, the problem is that we haven’t talked about all the market research.

As well as their 190,000 taste-tests, Coca-Cola had also done some qualitative research, with focus groups. Naturally, Coca-Cola had favoured their robust quantitative data over what groups of 12 random guys in some rooms somewhere thought. This turned out to be a mistake, because what the focus groups were telling them was that around 10% of people really hated the idea of Coke changing, irrespective of what it tasted like, and that those people bullied and peer-pressured the others in their group into agreeing with them. Their quant research told them that people loved the new drink, and the qual research told them that this was going to be a fucking nightmare. Both were right.

From an editorial viewpoint, “New product is basically fine,” is a far poorer story than reporting outrage over the change, and duly the voice of the minority was amplified. The Washington Post, which a decade earlier had uncovered the Watergate scandal, went with a measured approach to the introduction of a new soft-drink, “Next week they’ll be chiselling Teddy Roosevelt off the side of Mount Rushmore.” Meanwhile, readers in New York were told, “The new drink will be smoother, sweeter, and a threat to a way of life.” The Chicago Tribune called it absolutely correctly, “Changing Coca-Cola is an intrusion on tradition, and a lot of southerners won’t like it, regardless of how it tastes.”

In the South there were protests and boycotts, even cases of New Coke being poured down drains. Coca-Cola’s decision to launch the product in New York, which they saw as taking the fight to the enemy, was re-cast by Pepsi’s letter as a Southern company going to the North to surrender. Because the three most public people behind New Coke – Roberto Goizuerta, Brian Dyson, and Sergio Zyman – were suspiciously foreign – respectively, Cuban, Mexican, and Argentinian – rumours started that New Coke was a communist plot. Rumours, apparently, not dispelled by the world’s most famous communist Coke-drinker, Fidel Castro, denouncing New Coke as a symbol of capitalist decadence.

A pressure group formed, Old Cola Drinkers of America, founded by this gentleman…

The OCDoA claimed to have 100,000 members, and to be fighting for freedom of choice, the very nature of America. They launched a class-action lawsuit, to try to force Coca-Cola to either revert to their original formula or to sell it to someone who would produce it. They lost. Mr Mullins then appeared in a series of nationally televised taste-tests, where he demonstrated to the whole nation that he either couldn’t tell the difference between Coke and New Coke, or expressed a preference for New Coke. He then returned to suing Coca-Cola, claiming that his performance in the taste-tests (which, because I need to keep reminding myself this is true, were nationally televised) was due to his taste buds being destroyed by the high fructose corn syrup used as a sweetener in New Coke. He lost that case as well (most Coke bottling plants had switched to high fructose corn syrup years before New Coke, Coca-Cola just hadn’t made a song and dance about it).

Pepsi, meanwhile, were enjoying the sweetness of their rival’s suffering, churning out a new campaign that reenforced the idea that Pepsi had beaten Coke. Some of their adverts were so hastily made that it seems they didn’t even have time to cast people who could act.

With people now trying to import original Coke from overseas, and overseas markets, worried by the disruption in the US, getting nervous about accepting New Coke, which had been planned to roll out worldwide over the summer, Coca-Cola threw in the towel. On July 11th, just 79 days after the launch of New Coke, they announced that they would reintroduce their original formula, labelled as Classic Coke, alongside New Coke. The ABC network interrupted General Hospital with a newsflash, to let America know that Coke was returning.

Coca-Cola got their Hollywood ending. Sales of Classic Coke soared, and it ended 1985 comfortably outselling both Pepsi and New Coke, both products it was quantifiably less liked than. The conventional wisdom became that Coke was a foundational part of America and that people had simply forgotten how much they loved it, a story that Coca-Cola, unsurprisingly, embraced.

Their internal reports, however, revealed quite a different view. They had, they concluded, seriously underestimated the influence that could be wielded, and the damage that could be done, by a relatively small group of angry people.

I don’t think it’s unfair to say that, long before anyone ever used the term in this sense, before social media, even before the Internet had entered American homes, New Coke was cancelled.

It may be the first time we ever had all the ingredients of a modern cancellation in one place; an angry and vocal minority, the press fanning the flames, the argument being spuriously linked to whatever subject could give it unearned gravitas – the Civil War, Communism, freedom of choice – and a clear grifter being given national celebrity status. Most importantly, it won. Not just in terms of getting its immediate goals met, with the return of Classic Coke, but in the public recollection of what happened. A decision made for rational reasons, with ridiculous amounts of preparation, that resulted in a good product, which people liked, is remembered as not only the complete reverse of those things but as the archetype of the opposite.

It’s too late to save New Coke, it settled down to holding about 3% of the soft-drink market and was renamed Coke II in 1990, before being discontinued in July 2002. The following month Coca-Cola announced they were dropping the “Classic” branding, and after 17 years away, Coke was again just Coke. Perhaps, though, it’s not too late to remind ourselves that what people say they want, which voices the media choses to amplify, and what they claim to be fighting for might not be what they first seem, and may not represent what we would chose for ourselves, if we had a taste.

Final note, for the pedantic: There was not, in 1985, a product called New Coke. There was Coke, made to the old formula, which was replaced by Coke made to the new formula. Its common name, New Coke, came from the “New” flash that was printed on the cans, as seen in the photo of Roberto Goizueta. There was, however, a New Coke in 2019. In a tie-in with Stranger Things, Coca-Cola made 500,000 promotional cans, to the 1985 recipe. Demand for them was so high it crashed their website. Some things just won’t stay cancelled.