My life was shaped by random chance. Just like everyone else’s. In my case, it was that the availability of home computers coincided with my teenage years. My Christmas present the year I turned 13 was an Acorn Electron.

This was the computer that kept me up late at night, teaching myself to programme in BASIC, way before you could Google any problems you were stuck on. You had the user guide, Electron User magazine, your wits, and all the time you weren’t spending going out with girls.

I should add that, technically, it was a shared Christmas present with my brother. As it’s still sat in my garage, 42 years later, and he’s still waiting for his go on it, he kind of got hosed on that deal. For me, though, it gave me my career goal… I wanted to be a computer programmer.

It’s almost unimaginable now how untrodden that path was at the time. I took O-level computing at school, but I was in the first year for which that was even an option, and there wasn’t an A-level course to progress into. I started maths, physics, and chemistry A-levels – despite having no particular interest or aptitude in any of them – just because programming was loosely bundled in with “all that nerd stuff”. Then I tried college, for a BTEC in computing, which taught me the Pascal programming language but otherwise bored me (and suffered badly for coinciding with the time in my life when pubs started serving me).

By the arse-end of the 80s I’d ended up on an employment training programme. These were based around training companies, who taught you and then tried to find you placements with employers, with the hope it would lead to a full-time job. They paid handsomely; your dole money + £10 a week (for a grand total of £29!) AND a free bus pass! They taught me a bit more Pascal, added a couple of City & Guilds qualifications to my CV, and were lax enough that we got to spend a lot of time on Snipes

Then I became a programmer!

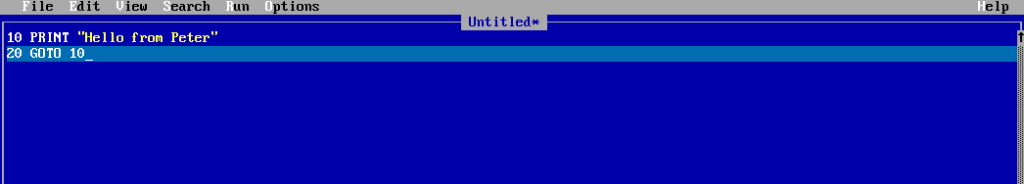

A company in Newcastle approached the training agency, and said they needed someone who could program in BASIC, and I was the only person they had. First, though, I had to go through a rigorous interview. My interviewer, Peter, fired up QBasic (the first time I’d ever seen it) and quickly typed in the follow program…

Then he ran it, to show me what it did, and asked me if I could modify the program, so that it said “Hello from Andrew” instead.

Reader, if you’ve never written a line of computer code in your life, if you’d never heard of the BASIC programming language until 7 paragraphs ago, if you’re so technically inept that your local branch of PC World has employed a bouncer, to keep you out, then I’m going to bet you could still make a reasonable stab at that challenge.

Anyway, I passed the interview and started the placement. And this is the part of the story where life is about to mug me.

You see, the problem with teaching yourself to code, with very little external input, is that it trains you to work to exactly one testing standard, “Does this program do what I expected it to?” The parts of my, patchy, formal education that I’d been bored to tears by were the bits where they were talking about standards and conventions, because I could honestly not understand the point. If your program worked then it worked, and you moved on to the next thing. Karma is about to teach me what college could not.

My new employer had one BASIC program. It was running on an ancient NCR (the people more noted for making electronic tills) machine, which was so near death that I had to end every day by backing the whole thing up, so that I could start the next day re-formatting the hard-disk, to get it through another 8 hours. It had a straight wire connection to a mainframe down the hall, and the only printer it supported was its in-built till-roll printer.

The program itself had been written by an external firm. An external firm who had immediately outsourced the entire job to the 14-year-old son of one of the people who worked there, who had clearly learned programming by exactly the same method I had. The resulting program was 7,000 lines long, and the entirety of the documentation for it was a single REM (comment) line at the start of the program, giving the name of the company that was to blame for this behemoth.

I spent the first 5 weeks of my 6-week placement printing out till-roll listings of the program, and gluing them to sheets of A4, drawing flowcharts of the program logic, creating lists of the variables and my best guess at what they were being used for (one of the fun aspects of this particular implementation of BASIC was that it only supported single-character variable names, which meant that most of them got re-used, for very different purposes, several times over).

To make matters worse, there was a brand new IBM PC, sat on the empty desk next to me. Multiple times I begged to be allowed to just re-write the program from scratch on it, and multiple times they refused, on the grounds that they didn’t think I had sufficient experience for that. With the benefit of 35 years of hindsight, they were right. I’d have given them a program with all the same problems, just on a different piece of hardware.

Anyway, it was only after this Herculean documentation task was completed that I could finally ask, “What do you want me to do with it?”

“Can you make it run a bit quicker?”

[Tech alert]For reasons of, I suspect, “This is cool”, the program used its own input routine, reading the keyboard buffer character-by-character, which meant when typing anything in there was a delay between hitting the key and the character appearing on-screen. I stripped this out and replaced it with BASIC’s in-built INPUT. The program didn’t do anything meaningful any faster, but it felt faster.[End of tech]

My employer was happy. Their program was slightly better than it had been, and they now had a think folder of documentation to go with it. They were so happy, in fact, that they offered to extend my placement, so I could carry on the good work.

I turned them down. Those 6 weeks had ended my desire to be a programmer. A love that had kept me awake in the early hours of the morning, editing lines of code on a 10″ black & white portable telly screen, was over. Those weeks were the last ever where I held a position that required me to be able to write a single line of code.

Why, you may ask, have we taken this stroll down memory lane? Because although I can’t feel that old love any more, I can still remember it. Remember the pleasure of the challenge of taking a human task and breaking it down into hundreds of tiny, logical steps. The joy of analysing and rationalising your thoughts so that they can be understood by a dumb orders-following machine. Programming might seem, from the outside, to be nerdy and dull, but that doesn’t mean that from within it can’t be passionate.

… And we’re on the verge of making the job of all new programmer that of understanding the 7,000 lines of code that an AI has spat out. Painstakingly working out, line by line, what it’s done, so that minor tweaks can be made, while telling them that they don’t have the requisite experience to do the job from scratch.

This is why AI is the worst thing that we’ve ever invented. Not because it hallucinates answers, or wrecks the environment with its power and water demands, or steals content, or even takes jobs. It’s because it takes what we love, be it art, or literature, or even writing computer programs, and kills it.

I lost my first great love but I did not lose my humanity, so I will never support AI, the love-destroying machine.